- Home

- Maile Meloy

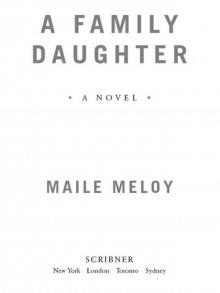

A Family Daughter

A Family Daughter Read online

Also by Maile Meloy

Liars and Saints

Half in Love: Stories

The author wishes to thank the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the Santa Maddalena Foundation for their generosity during the writing of this book.

SCRIBNER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2006 by Maile Meloy

All rights reserved, including the right of

reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SCRIBNERand design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work.

Designed by Kyoko Watanabe

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meloy, Maile.

A family daughter : a novel / Maile Meloy.

p. cm.

I. Title.

PS3613.E46F36 2006

813’.6—dc22 2005051574

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-8901-6

ISBN-10: 0-7432-8901-3

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

And Nature in her perplexingest mood would not of herself cast me as a family daughter.

—MARYMACLANE

Part One

1

IN THE SUMMER OF 1979, just when Yvette Santerre thought her children were all safely launched and out of the house, her granddaughter came to stay in Hermosa Beach and came down with a fever, and then a rash. Yvette thought it might be stress: Abby was seven, and her parents were considering divorce, and she must have sensed trouble. At bedtime she cried from homesickness, and Yvette asked if she wanted to go home. Abby said, “I want to go home, and I want to stay here.”

The rash got worse, and Yvette’s husband said they should tell Clarissa her daughter was sick. But Clarissa had gone back to Hawaii, where she had lived in Navy housing before Abby was born. She said it was the last place she had been happy, and she was staying somewhere without a telephone. So Yvette called Abby’s father, up in Northern California.

“Oh, man,” Henry said, when he heard.

“Was she exposed to anything?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Let me talk to her.”

“I think she has chicken pox.”

“No, she can’t have chicken pox,” Henry said. Yvette imagined him on the other end, big and sandy-haired and invincible. It was one of the infuriating things about Henry: he thought he was immune to bad luck, and by extension his daughter was, too.

“Has she had it before?” Yvette asked.

“I don’t think so,” he said.

“Well, then, she can have chicken pox.”

“Did you take her to the doctor?”

“I raised three children, Henry,” she said. “I don’t need a doctor to recognize chicken pox.” Mrs. Ferris next door had already quarantined her own daughter from Abby. Yvette hadn’t heard anything about an outbreak in Los Angeles.

“Put Abby on,” Henry said.

Yvette gave the phone to the child, who held the receiver to her ear with both hands. Abby nodded, in answer to some question of her father’s.

“You have to say it aloud,” Yvette said. “Say yes .”

“Yes,” Abby said, into the phone. She turned toward the kitchen wall to have the conversation on her own.

Yvette washed Teddy’s breakfast dishes and thought her husband seemed annoyed to have a sick child in the house again. It took her attention and drained her energy. She didn’t want a divorce for her daughter, she wanted a time machine. There would be no Abby, without that dominating Henry, but there would be some other child—a happier child—and a marriage that wasn’t doomed from the start. Her older daughter, Margot, had a husband who was kind and stalwart and patient: if only Clarissa had found a man like that. Yvette tried to accept that the way it had gone was God’s plan.

Abby said good-bye to her father, and Yvette took the phone.

“I want you to take her to a doctor,” Henry said.

“He’ll want to know when she was exposed.”

“Well, I don’t know that,” he said.

“Do you know where I can reach Clarissa?”

“Clarissa won’t know.”

“It’s not going to be a very nice summer for Abby.”

“Look,” Henry said, “if she has chicken pox, it’s not my fault. Kids get it sometime, right? And if she got some mystery rash at your house, it’s really not my fault. Just please take her to the doctor and find out.”

Yvette said tightly that she would.

Dr. Nye, in his office with poor Abby sitting shirtless on the white table, confirmed that it was chicken pox. He was a white-haired man in a clean white coat, who reminded Yvette of a parish priest back in Canada when she was a child. He wanted to know when Abby had been exposed.

“At least ten days ago,” she said. “The only child she’s seen here is Cara Ferris.”

“Can I play with her yet?” Abby asked. Cara lived next door, and had blond ringlets, and had marched at the head of the Fourth of July parade, twirling a baton, as Miss Hermosa Beach Recreation. Abby worshiped her.

“Not until you’re better, sweetheart,” Yvette said.

“But Cara’s had chicken pox,” the doctor said.

“Her mother said it was such a slight case she could get it again.”

Dr. Nye made a little scoffing noise. “Just keep Abby home,” he said, “and use calamine. I’ll pronounce her not contagious as soon as I can, and she can play with Miss Recreation.”

The next day a heat wave started that broke Los Angeles temperature records, even in the beach towns. The air was stifling, the sky was pale with smog, and poor Teddy left for work, miserable in his dress shirt and tie. The best refuge was the pool, surrounded by cool sycamores, where the children played Jump or Dive, shouting at the last second what the child launched from the diving board should do and squealing with laughter at the midair scramble to obey. Abby lay on the living room couch, banned from the pool, staring miserably out the window as Cara pranced to the car in her blue swimsuit and her yellow curls, a rolled-up towel under her tanned little arm.

They still didn’t know where Clarissa was. Yvette talked to Teddy about it in bed, but he was too tired to be worried. He had too much work, and was ready to retire. She stayed home with Abby on Sunday, and Teddy went to Mass alone. She knew it was dangerous to compare sisters, but Margot wouldn’t have sent a sick child without warning. She had devoted her life to raising her two boys, and she would never be unreachable about them.

On the fourth day, Clarissa finally called. Polka-dotted with dried calamine lotion, Abby told her mother she couldn’t go to the pool and then went back to doing puzzles in a book. Yvette took the phone.

“I think one of the neighbor kids might’ve had it,” Clarissa said. “I forgot.”

“She’s your child. She’s your first obligation.”

“Don’t start,” Clarissa said. “I’ve been so unhappy.”

“Everyone is unhappy sometimes.”

“I didn’t know—” Clarissa began and trailed off.

“What?” Yvette snapped. “That there were responsibilities?”

“That my marriage would fall apart. That there would be such killing boredom. That I wouldn’t get to do anything I wanted to do. I didn’t know!”

Yvette stood at the kitchen counter wondering what part of her daughter’s selfishness was her fault. Had she not given Clarissa enough

attention when she was Abby’s age? Had her other children distracted her—Margot, who was older and perfect, and Jamie, who was younger and troubled? Yvette took a deep breath. She would love her daughter as God loved them both, with all of their flaws. “Are you finding what you want, there?” she asked.

“No,” Clarissa said. “I’m in the most beautiful place in the world, and the first time I call, my kid has chicken pox. So I feel guilty and horrible . And I’ve felt guilty and horrible all week just in anticipation of something . I knew there was going to be something like this.”

“You sound like you think it’s my fault,” Yvette said.

“No,” Clarissa said, unconvincingly.

“I’m not asking you to come back,” Yvette said. “She’ll get better.”

“I didn’t think she’d get sick. She has to play with someone. That time alone is my sanity.”

When Yvette hung up, she took a fresh glass of juice to the living room, where Abby lay on the couch reading a comic book. She was at the age to have communion, and she wasn’t even baptized.

“Your mom said good-bye and to tell you she loves you,” Yvette improvised.

“Where am I going to live now?”

Yvette pushed Abby’s hair from her face. “I think you’ll live with your mom.”

“In Hawaii?”

“No, I think at home,” Yvette said.

Abby looked at her pink-splotched knees. “With just my mom?”

Yvette sighed. “I don’t know, sweetheart,” she said.

Yvette kept the drapes drawn to keep the house cool, and the dimness increased Abby’s gloom. Yvette tried to teach her to crochet, but Abby got frustrated with the yarn. They played Boggle and Go Fish. Sometimes, in bored wanderings through the house, Abby took pictures off the master bedroom wall and lay on the bed looking at them. She liked Yvette’s wedding picture, with Teddy in his pilot’s uniform during the war. And she liked a picture of the two girls: Clarissa with her dark hair coming out of its curls, and Margot standing behind her, polished and serene. Abby would study the pictures and then hang them back on the wall and turn on the TV. In the heat wave they were airing Coke and Pepsi and 7UP commercials, and Abby had memorized them all. She sang the jingles absently in the bath. It was killing Yvette.

At the end of the week, Yvette called Jamie, her youngest, who was in college in San Francisco. She begged him to come home.

“I’m taking a summer class,” Jamie said.

“You should see her,” Yvette said. “She’s so miserable. Mrs. Ferris won’t let her play with Cara. I could just wring that woman’s neck.”

“My car might not make it.”

“I’ll send Triple A,” Yvette said.

He was home by late afternoon, with a duffel bag full of laundry that he dropped on the kitchen floor. Her handsome, mischievous boy: he had caused her so much trouble over the years, but now he had come when she needed him. She kissed his cheeks out of gratitude, as Abby sidled into the kitchen.

“Where’s my favorite niece in the whole world?” Jamie asked.

Abby wrinkled her nose at him. “I’m your only niece.”

Yvette noticed that Abby had washed the calamine off her face and arms, in honor of Jamie’s arrival. She still had spots, but she didn’t look like she was dying of a pink plague.

“Oh, yeah,” Jamie said. “Well, if I had others, you’d still be my favorite. Want to hit the beach?”

“People might think I’m contagious,” Abby said, solemnly.

“Are you?”

She shook her head no.

Jamie shrugged. “So who cares what they think?”

“I can’t go in the waves alone,” Abby said, more hopeful.

“I’ll carry you in,” he said. “Let’s go, get your suit on.”

Abby turned and nearly danced down the hallway to her room.

“Thank you,” Yvette said to Jamie. “I can’t tell you—”

“No biggie,” he said, opening the refrigerator. “That class was a drag anyway.”

“Was it? I’m sorry.”

“It’s pretty much your fault,” he said, but she could tell he was joking.

“You can take another class later.”

“Sure.” He closed the refrigerator.

“I’ll go shopping.”

“Looks good, Ma,” he said. “I was just checking. Here she is, let’s go.”

He lifted Abby in her blue swimsuit onto his hip, as if she weighed nothing, and carried her out to the red Escort that used to be Teddy’s.

Yvette followed with a twenty from her pocketbook. “After the beach, you can bring back ice cream for dessert.”

Jamie snapped the bill for Abby. “Score!” he said.

Two hours later they came back, Abby sandy from the beach, with a tub of Dairy Queen ice cream and some Dilly bars that they rushed to the freezer. Abby chatted happily all through dinner, and it seemed to Yvette as if her cheerfulness were a wheel that Jamie had gotten spinning. Now he just needed to give it a push every so often, to keep it going.

“Thank you, Jamie,” Yvette said, when she got her son alone. She couldn’t remember when she had last thanked him for anything but Christmas presents, and now she couldn’t stop.

Jamie moved into his old room and took Abby to the beach every morning. In the afternoons, he taught her five-card stud, sitting at the kitchen table with piles of unshelled peanuts.

“No eating your chips,” he told her, “or we won’t know who wins.”

“You’ll win,” she said.

“I might not,” he said. “I think you have a real talent for the bluff.”

“No, I don’t.”

“You do!” he said. “Or you will when I get through with you. We can go on the road and win big—you’ll be the perfect hustler.”

Abby laughed. Anything Jamie said was funny; anything he did was fun. He played guitar for her, making up songs with her name in them, and he made chords and let her strum. He listened to records in his room, and Abby sat on the floor, her dark head bent over the album covers.

One afternoon, Yvette was collecting laundry from Jamie’s room, and his new Bob Dylan record was playing. Abby was studying the cover. Jamie lay on the bed, reading his old paperback copy of Dune . Bob Dylan sang:

You may be living in another country, under another name

But you’re gonna have to serve somebody.

“Why would you have another name?” Abby asked. Yvette took a towel off a doorknob.

“I guess if you did something wrong,” Jamie said.

“So they wouldn’t find you?”

“Right,” Jamie said.

“But if they saw you, they would know you.”

“That’s why you live in another country.”

Yvette bundled Jamie’s clothes under her arm and said, “I live in another country, under another name.”

Abby looked at her, astonished, and whispered, “Why?”

“I married Teddy, when he was a pilot in the war,” Yvette said. “And I moved here from Canada and changed my name to his.”

“That’s not the same thing,” Jamie said. “She didn’t do anything wrong.”

But it had felt wrong, leaving her father, who hadn’t wanted her to go. “I did leave my family and my country,” Yvette said. “And I never went back. I always thought I would.”

Jamie shrugged in grudging acceptance. “Okay,” he said to Abby, “so the song’s about your grandma. It’s about Canadians getting married and moving to California and serving the war effort and the holy Trinity.”

“Oh, Jamie, ” Yvette said, and she laughed, embarrassed, and took the wash to the machine.

Yvette cooked Jamie’s favorite meals—enchiladas and chiles rellenos for dinner, poached eggs and toast soldiers for breakfast—and they became Abby’s favorites. When Clarissa or Henry called, Yvette was careful not to praise Jamie too much and make them feel they were being replaced, because she didn’t see any benefit to their rec

laiming their daughter yet. Abby was blissfully happy, and Jamie had a devotee and a life at the beach. If Henry was working, and Clarissa was off finding herself, then they were all where they wanted to be.

2

HENRY DIDN’T WANTthe divorce. Clarissa was his wife and he loved her, even if she wasn’t all there, all the time.

There was the time, for example, when Clarissa wandered away from the kitchen sink, where she was washing nursing bras with the baby lying on the drainboard. While she was gone, Abby rolled with a splash into the soapy water and had to be hauled out wailing. Or there was the time Clarissa left their daughter, at three, strapped in the backseat next to a roll of insulation for the house while she ran some errand. By the time Clarissa got back, Abby had hives all over her wrists from playing with the pink fluff. “Fiberglass,” Abby announced; it was written in big letters on the roll, and was the reason Clarissa reported the story proudly to Henry.

“I hadn’t said it in front of her,” Clarissa said. “I know she read it. Isn’t that amazing?”

“Clar, you can’t just leave her in the car!” he said. “Someone’s going to call the cops!” People in Santa Rosa paid attention to their neighbors.

“Well, we’ll just show them she can read, at three,” Clarissa said, getting sullen. “At least I had her seat belt on. And it’s none of their business.”

Henry had grown up in Santa Rosa, and buried his parents there. He had goodwill there, people who had known him all his life. It was only an hour north of San Francisco, a good place to start a law practice, a good place to raise children. When he got out of the Navy in Honolulu, it was only natural that he would go back.

But from the moment they had unpacked their books and hung some pictures on the walls, Clarissa—already pregnant—started complaining it was too small, too restrictive, too provincial. She wasn’t able to fulfill her potential. Henry thought she should be busy having his baby, but he didn’t say so. The complaint came up again, in those early years, but Clarissa’s only decisive act was to go to Hawaii and leave Abby with her parents with the chicken pox. During an argument after she came back, when the separation was still just an option, Henry had asked what exactly she imagined her potential to be, but that was a mistake—she left him the next day, and moved to San Francisco to take classes at the university. She said it would be better for Abby to stay in a house she knew. Henry found himself suddenly a single parent.

The Apothecary

The Apothecary Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It

Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It Do Not Become Alarmed

Do Not Become Alarmed Devotion: A Rat Story

Devotion: A Rat Story A Family Daughter

A Family Daughter